What We Can Learn From Washington’s History of Revolutionary City Planning

The Washington, D.C. area is admired around the world for its parks, monuments, stately architecture, and attractive urban spaces. But the region would look very different if it were not for the bold, innovative thinking that guided its planners nearly 120 years ago.

At the turn of the 20th century, American cities typically grew in market-driven, haphazard spurts. Water and sewage systems were managed by public authorities, but few other aspects of urban development were subject to any coordinated planning.

Washington became an exception. In 1900, the Board of Trade organized a lavish event to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the District becoming the nation’s capital. This was an inflection point for the city, which had become a source of national pride. Prominent Washingtonians asked themselves, how could the city better represent the culture and values of the United States?

At the time, the American Institute of Architects believed that the capital should be shaped by the nation’s best architects and artists. They envisioned grand, beautiful, and aesthetically unified buildings and public spaces. They sought the “American Renaissance” style, which embodied public order, progress, refined taste, patriotism, national wealth, and power.

Meanwhile, the Board of Trade pushed a strategy focused on parks. A large and well-maintained network of parks would ensure that individuals and families had access to natural spaces as the city grew in population. Indeed, our region’s park system has had a positive effect on air and water quality, public health, social ties, and even our local economy by making the region a more attractive place to live, work, and visit.

In 1900, Senator James McMillan introduced a resolution in the Senate that would accommodate varying viewpoints on design improvements to the capital. With the support of the Board of Trade, the resolution called for the president to appoint a panel of professional artists and architects who would work together to design the National Mall as well as a system of parks within and around the District.

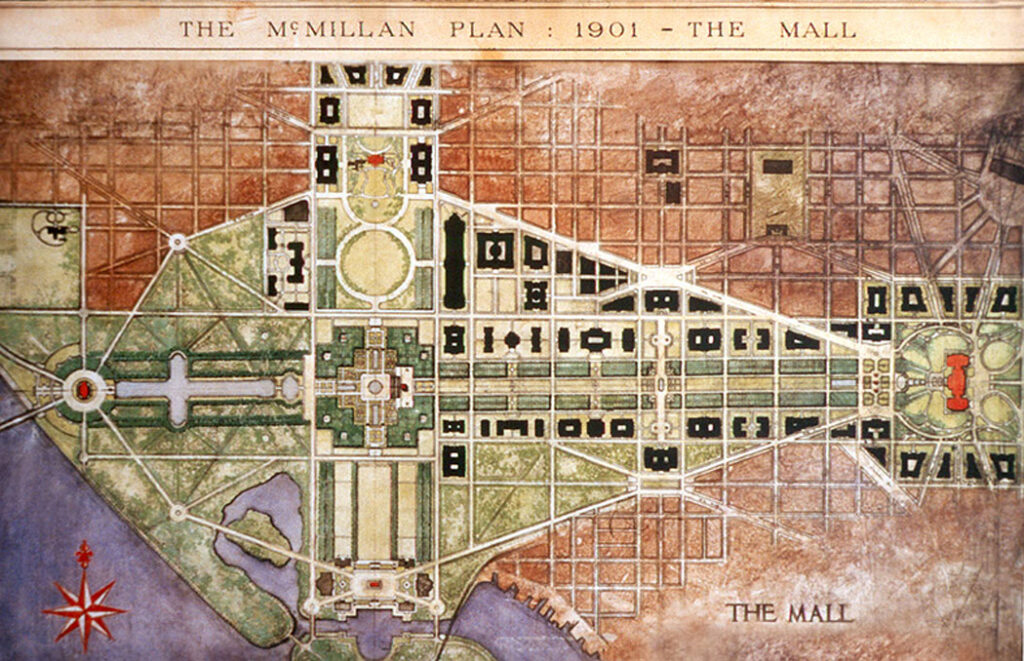

The result was the radically comprehensive Senate Park Commission plan, also known as the McMillan plan, which guided continuous development of the nation’s capital over many decades. The plan transformed the Mall from a disjointed collection of smaller parks into a grand grassy lawn surrounded by historical museums, elm trees, fountains, and monuments. It replaced miscellaneous red brick buildings with stately white neoclassical ones. It removed a railway station on the Mall and replaced it with a large, modern station north of the Capitol Building—which is now Union Station. It called for new office buildings for federal agencies to be built in Lafayette Square and Federal Triangle. It included the Memorial Bridge across the Potomac River. And it established a huge network of public parks, playgrounds, and other public outdoor amenities, all connected by a series of parkways and extending out as far as Rock Creek Park, Great Falls, and Mount Vernon. Residents and visitors now enjoy these unique places and resources, most of which are maintained for all Americans through the stewardship of the Department of the Interior.

The scope of the McMillan plan was massive, which was not originally the objective. Senator McMillan had asked the team of architects to put forward a preliminary plan outlining incremental improvements to the area because those were more likely to get funded by a fiscally conservative Congress. But the team didn’t listen. They instead laid out their vision for the whole region and sought both function and beauty. They designed for the whole, not just the parts. Their bold, innovative thinking made the Senate Park Commission plan one of the most influential urban plans in American history.

This story is a reminder to think big. Local politics, funding concerns, and competing interests can marginalize great ideas. Our tendency to label bold visions as unrealistic dissuades us from thinking ambitiously. In recent years, this has held our region back from tackling tough problems related to transportation, housing affordability, social inequities, and other factors that impact quality of life.

The Greater Washington Smart Region Movement is our next chance to think big. Our vision is for a region that seamlessly uses digital technology to operate more smoothly while making life better for the people who live, work, and play here. To get there, we’ve formed an exceptionally inclusive coalition of organizations—nonprofits, companies of all sizes, academic institutions, government agencies—to design a strategy that serves the whole region. It will be a long and complicated process and we sincerely appreciate the dedication and support of our members and the broader community.

I’m grateful that the Board of Trade and the team of architects behind the Senate Park Commission plan allowed themselves to boldly and responsibly envision a better future, and I know that the work we are doing now will have the same positive impact on the generations ahead.

Become a member today

We need your voice at the table to make Greater Washington a place where everyone can succeed